The double slit experiment of quantum mechanics “has in it the heart of quantum mechanics” and “contains the only mystery,” states the Nobel laureate creator of quantum electrodynamics Richard Feynman.

“All of quantum mechanics can be understood by pondering the implications of the double slit experiment,” Feynman has also said.

The double slit experiment clearly demonstrates nothing but the fact that the universe’s subatomic particles are created upon observation in an uncaused manner. Such a thing can only be rationalized by accepting the fact that the universe exists in the minds of its observers, as we’ll elaborate.

The insanely counterintuitive behavior of subatomic particles about to be described with the help of the double slit experiment illustrates the fact that subatomic indeterminacy and inability to predict exact outcomes is a direct consequence of the wave/particle duality of all matter. It’s the wave/particle duality that requires a wave equation to represent how all subatomic particles behave, as will be demonstrated.

In 1704, Isaac Newton published that light must made of particles. But despite the way Newton’s particle model successfully explains the basics of optics including optics within lenses and through pinholes, it was challenged by a wave model by physicists who had noticed light’s ability to also exhibit wave phenomena such as diffraction and interference. Light was believed to be a wave phenomenon until the end of the 19th century, when the particle model was revived by Einstein who established that light must exhibit both particle and wave characteristics depending on circumstance. This discovery brought Einstein the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics, but there were still many unanswered questions.

After Einstein had demonstrated the fact that light can exhibit both wave and particle characteristics, French physicist Louis de Broglie went further to postulate that not only light, but all particles of matter such as electrons, protons, etc. exhibit both wave and particle characteristics. De Broglie's hypothesis was experimentally confirmed in late 1920s. Richard Feynman summarizes the developments:

“The gradual accumulation of information about atomic and small-scale behavior during the first quarter of the 20th century … produced an increasing confusion which was finally resolved in 1926 and 1927 by Schrodinger, Heisenberg, and Born. They finally obtained a consistent description of the behavior of matter on a small scale.”

How, exactly, was the increasing confusion resolved about the wave and particle characteristics of matter, resulting in the formulation of the indeterminacy principle requiring uncaused events, yielding the birth of the probabilistic physics called quantum mechanics?

For the answer, I’d like to move on to describing the single experiment demonstrating “the basic element of the mysterious behavior in its most strange form,” as Feynman has put it, demonstrating the reality of uncaused events and the impossibility of eliminating them.

THE DOUBLE SLIT EXPERIMENT

1. THE BEHAVIOR OF PARTICLES

To expose the central mystery “in its most strange form,” letting one see how uncaused events arise, I’d like to refer mainly to Nobel laureate physicist Richard Feynman’s famous lecture notes. I’ll describe what I believe is a clearer version of these notes every layman can effortlessly follow, explaining the origin of the wave/particle duality and the indeterminacy principle it yields.

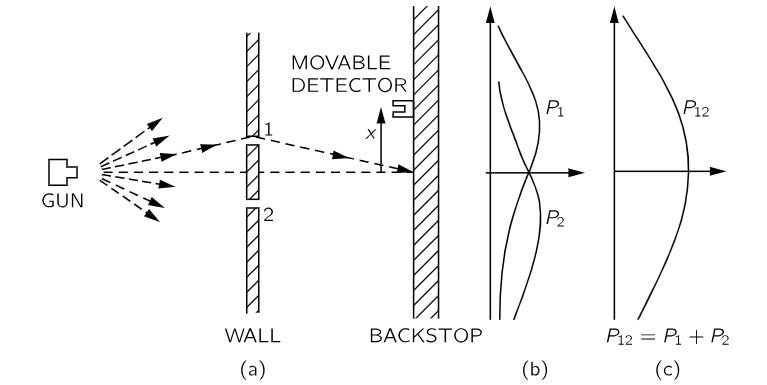

In his lecture notes explaining where the indeterminacy principle comes from, Feynman first describes a version of the double slit experiment illustrating the defining characteristics of particles (versus waves). To show how particles behave, Feynman describes the behavior of discrete bullets fired randomly from a gun at a wall containing double silts in front of the gun as shown in the figure below.

In this experiment with bullets, the “gun” used is not a regular gun which shoots straight ahead, but a “gun” which randomly scatters the bullets over a large angular spread as shown in the figure. Whichever direction the bullets go after being fired, some make it to the backstop after getting reflected off the sides of the 2 slits in the wall in front of the gun. The backstop has a detector that can be moved along it in the vertical direction, allowing the accumulation of the bullets. This detector could be a box containing sand, says Feynman. Such a movable detector allows counting how many bullets arrive at the backstop at each position along it.

To understand this experiment, laymen may need to learn a simple but important principle of probability theory called the law of large numbers. This main principle of statistics can best be explained by the example of a coin being tossed to see which side up it lands. Since the coin has equal probability of falling heads side up or tails side up, the probability of getting tails side up would be 0.5 (half the time) and the probability of getting heads side up again 0.5 (half the time). But one may not be able to see the coin land heads up half the time and tails up half the time if one flipped the coin too few times, one can see the coin land heads or tails up approximately half the time if one repeats the experiment a large number of times. For example, if the coin is flipped only 5 times, one may get 1 tail and 4 heads, or 5 tails in a row and no heads, etc., but if the coin is tossed 1000 times, the frequency of getting tails and heads both would get closer to 0.5. If the coin is tossed 10,000 times, the frequency of getting tails and heads would get even closer to 0.5. Thus the law of large numbers states that the larger the number of times a probabilistic process is repeated, the relative frequencies of its possible outcomes get closer to their respective probabilities.

With the above in mind, let’s return to the version of the double slit experiment with bullets (particles) and see what happens when the bullets are allowed to hit the backstop while both holes are open, allowing the bullets to accumulate in the detector being moved along the backstop. Assuming the gun always shoots at the same rate, Feynman points out the way leaving the detector at any specific position of the backstop long enough and letting a large enough number of bullets accumulate at each position would let the relative frequencies of the number of bullets hitting each position approach their respective probabilities.

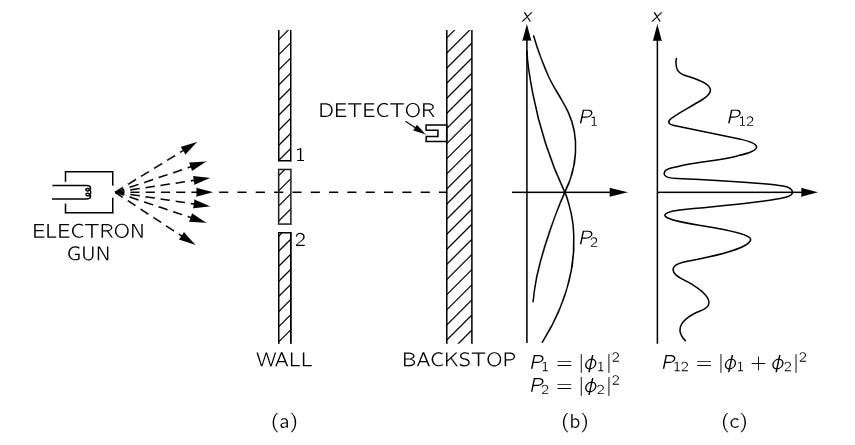

Obtaining the probabilities for the particles hitting each position along the backstop as described and plotting these probabilities yields curve P12 which peaks at the center as shown (see figure above). This curve is called P12 because the bullets may have come either through hole 1 or through hole 2 that are both left open.

Feynman then describes what happens when hole 2 is covered, letting one know that all of the bullets hitting the backstop must have come in through hole 1. This yields probability curve P1 for how many bullets hit the backstop at each position along it (see figure). The experiment is then repeated with this time hole 1 covered, letting us know that all of the bullets hitting the backstop must have come in through hole 2. This yields the probability curve P2 for how many bullets hit the backstop at each position along it.

Feynman points out that in such an experimental setup, the following applies to all discrete particles large and small:

- When both hopes are open, the probability that a bullet arrives at the backstop by passing through either hole 1 or hole 2 is equal to the probability of the total number of bullets hitting the backstop, which can be obtained by simply adding the number of the bullets that have gone through hole 1 (with hole 2 closed) and the number bullets that have gone through hole 2 (with hole 1 closed) for each position along the backstop. This makes the height of the probability curve P12 equal the algebraic sum of the heights of P1 and P2 as shown in the figure. This result, Feynman emphasizes, must always hold true for all kinds of particles.

- All particles are always detected as discrete lumps, versus the continuous nature of wave phenomena. Feynman describes the discrete nature of particles by saying, “if the rate at which the machine gun fires is made very low, we find that at any given moment either nothing arrives, or one and only one—exactly one—bullet arrives at the backstop. Also, the size of the lump certainly does not depend on the rate of firing of the gun [as it would in the case of wave phenomena]. We shall say: “Bullets always arrive in identical lumps.””

- Particles also never exhibit any behaviors such as diffraction or interference known to characterize wave phenomena. How wave phenomena does exhibit these behaviors is illustrated in the next version of the experiment conducted using water waves instead of particles.

2. THE BEHAVIOR OF WAVES

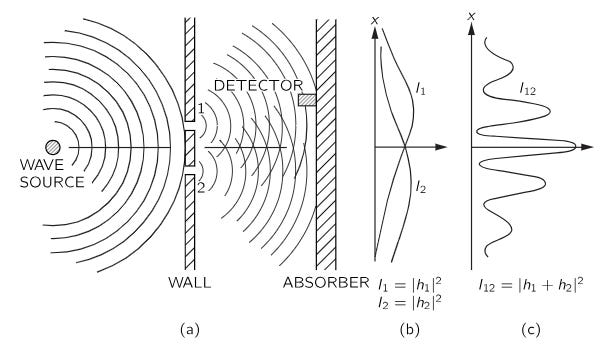

To contrast the behaviors of particles with those of waves, Feynman describes the same double slit experiment done in a water basin, with the gun firing bullets replaced with a motor jiggling up and down to produce circular water waves.

The backstop with the movable detector on it is now called an absorber (see figure) due to its ability to prevent the arriving waves from reflecting off it, to avoid complicating the experiment. The detector that can move along the absorber in the vertical direction can now detect the heights of the arriving waves which yield the intensity (proportional to the energy) of the wave motion. For simplification purposes, one can imagine the moveable detector as a cork placed very close to the absorber bobbing up and down in the water as each wave arrives, moving higher or lower indicating the height of each wave yielding its intensity.

As the detector gets moved to different positions along the absorber and the waves are allowed to hit it for long enough periods of time, one can get the rate at which energy is carried to the absorber (intensity) at each position as a mean over time, yielding the probabilities for the average wave intensity at each position along the absorber.

The experiment is first done with both holes open just like before. But as the waves pass through both holes, instead of simply bouncing off the sides of the holes to reach the absorber, they exhibit 2 behaviors called diffraction and interference described below, which are never exhibited by particles.

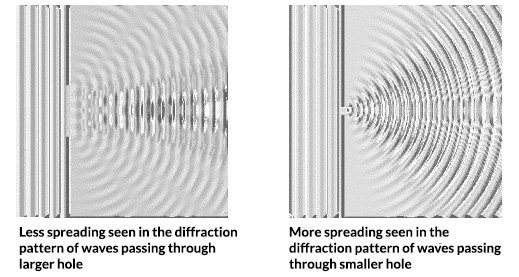

Diffraction refers to how obstacles cause waves to bend. The waves passing through the 2 holes diffract to form 2 sets of new circular waves as shown in the figure. The amount of the diffraction depends on the hole size, with a smaller hole size yielding larger amounts of spreading in the diffraction pattern.

As the waves diffract to form smaller circular waves after passing through the holes, they also interfere with each other. Interference refers to the ability of waves to reinforce each other when their crests overlap, or to cancel each other when their crests meet troughs. When the crests of the waves overlap, this is called constructive interference, which yields higher resultant intensities. When crests meet troughs, this is called destructive interference yielding lower resultant intensities.

After the waves pass through the 2 holes and interfere in ways reinforcing and cancelling each other by varying amounts as described, one gets the resultant intensity distribution curve I12 plotted for each position along the absorber (see figure above). After I12 is plotted, the experiment is repeated with hole 2 closed just like before, letting one know that all of the waves arriving at the absorber must have come in through hole 1. This yields the intensity distribution I1 for each position along the absorber. The experiment is then repeated with hole 1 closed, letting one know that all of the waves hitting the absorber must have come in through hole 2, yielding the intensity distribution I2 for each position along the absorber.

As one may note in the figure above, the height of I12 looks nothing like the simple algebraic sum of the heights of I1 and I2 as in the case of particles. There are places where the resultant wave heights are much greater than the algebraic sum of the heights of I1 and I2 due to constructive interference, and there are places where the resultant heights are almost zero due to destructive interference. Feynman points out the way I12 can be obtained form I1 and I2 not by adding the heights of I1 and I2 but only with the help of the mathematical formula for wave interference. All of this demonstrates that:

- All waves are capable of interfering with each other as described, getting reinforced or cancelled by each other according to the interference formula Feynman includes in his lecture notes.

- Waves are never detected in discrete identical lumps like particles, the intensity of the waves can have any value. For example, if the motor producing the waves vibrates a very small amount, less intense or less energetic waves arrive at the absorber but the energy can have any value without being restricted to any specific amount as in the case of particles. When the motor vibrates more vigorously, the waves detected at the absorber can have greater intensity or more energy, but the energy can again have any value without being restricted to any specific amount.

After having demonstrated the defining characteristics of all waves and particles, Feynman moves on to the version of the same experiment done with electrons, demonstrating the reality of the counter-intuitive wave/particle duality yielding uncaused events.

3. THE BEHAVIOR OF SUBATOMIC PARTICLES

In this version of the double slit experiment, electrons are used instead of bullets or waves. Just like the bullets, the electrons are fired one at a time and hit the detector one at a time. The detector gets moved along the backstop just like before, letting one count the number of the electrons arriving at each position along the backstop. The detector can be an electron multiplier connected to a loudspeaker, allowing one to hear a sharp clicking sound each time an electron hits it, says Feynman.

Just like before, the electrons are first allowed to pass through the wall when both holes are open. The experiment is then repeated by closing hole 2, and then repeated again by closing hole 1. The probability distributions for each of the 3 cases are plotted for the arrival of the electrons at each position along the backstop.

In this setup, Feynman points out:

- Whether both holes are left open or only one of the holes is left open, the electrons arriving at the backstop are always detected in identical discrete lumps indicating the presence of particles. This is because if one lowers the temperature of the wire in the gun emitting the electrons, the rate the detector clicks slows down but the intensity of the sound of each click doesn’t decrease as it would in the case of wave phenomena. Also, as the electrons get fired from the “gun” one at a time, if one were to place two detectors at the backstop, either one or the other detector would click but never both at the same time as in the case of wave phenomena. Thus one knows the electrons arriving at the backstop are particles.

- Since the electrons are always detected in identical discrete lumps indicating the presence of particles, one would assume that the height of the probability curve P12 at each position along the backstop should equal the algebraic sum of the heights of P1 and P2 obtained for the bullets when hole 2 and hole 1 were closed respectively. But instead of the heights of P1 and P2 adding up to P12, P12 can derived from P1 and P2 just like I12 can be derived from I1 and I2 using the formula for wave interference. This contradicts the fact that the electrons are always detected as particles at the backstop.

- Strangest of all, the wave interference pattern is observed despite the fact that the electrons get fired from the “gun” one at a time. This means that the interference pattern does not result from multiple electrons interacting with each other, but results form single electrons “interfering with” themselves like waves do on their way to the backstop, where they’re always detected as particles in the most mysterious manner.

What on Earth could be happening to an electron on its way that causes it to interfere with itself like a wave, before it mysteriously turn into a particle at the backstop?

Could there be any way to explain P12 other than with the mathematical formula for wave interference?

Feynman explains that there have been many ideas proposed to explain distribution P12 in ways other than with wave interference, but none of them have succeeded.

“We conclude the following,” says Feynman, summarizing:

“The electrons arrive in lumps, like particles, and the probability of arrival of these lumps is distributed like the distribution of intensity of a wave. It is in this sense that an electron behaves “sometimes like a particle and sometimes like a wave.””

The above is why in Britannica, 'de Broglie waves' of the subatomic realm are defined as “any aspect of the behavior or properties of a material object that varies in time or space in conformity with the mathematical equations that describe waves.”

In this experiment where each electron interferes with itself like a wave, and where the probability of each electron’s arrival at the backstop is distributed like the distribution of the intensity of waves, as each electron is nevertheless detected at the backstop as a particle, what could be happening to each electron to cause it to transform from a wave into a particle?

To find out the answer, in this setup letting the electrons reach the backstop only via hole 1 or hole 2, why not “look” at what happens by putting detectors near these 2 holes too?

Should be simple enough to do, right?

But whenever one tries to “see” exactly which hole the electrons pass through with any type of observation apparatus whatsoever, the central mystery takes “its most strange form.”

Brace yourselves.

4. STRANGER THINGS

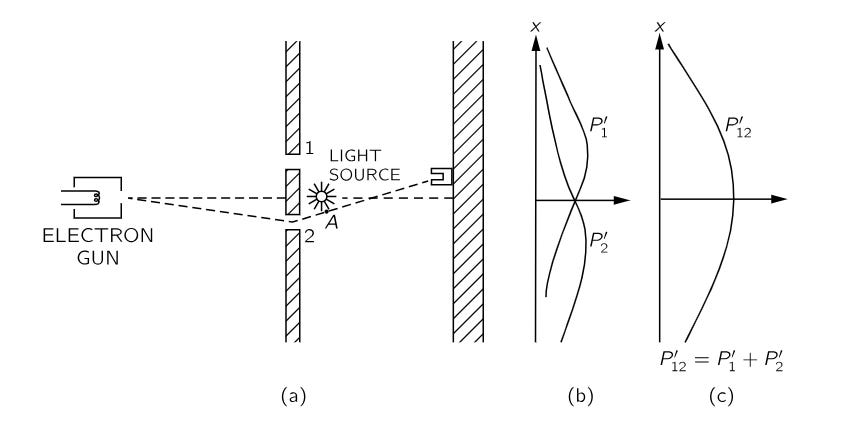

In the double slit experiment conducted with electrons, to see which hole the electrons go through on their way to the backstop, Feynman suggests putting a light source in the middle of the 2 holes behind the wall (see figure) in front of the gun. As electrons scatter light, this should let one see a flash near hole 1 or near hole 2 as an electron passes through that hole.

Would flashes be seen at either one of the holes or both of the holes at the same time if an electron divides in half or whatnot causing it to interfere with itself?

When the experiment is performed first with both holes open just like before, “every time that we hear a 'click' from our electron detector (at the backstop), we also see a flash of light either near hole 1 or near hole 2, but never both at once!” states Feynman, indicating that all the electrons arriving at the backstop must have passed either through hole 1 or hole 2 without having divided in half or done anything weird. So far so good.

As the electrons go through either hole 1 or hole 2, one always sees the same sized flash in discrete bursts. This indicates the presence of particles going through the holes, consistent with the way the electrons are also observed as particles at the backstop. What could be so strange about any of this?

To see what seems to completely defy reason and logic in this scenario, one may note that despite the way the detector near the holes always registers the electrons as particles on their way to the backstop, in the previous version of the experiment, we’d seen the wave interference pattern emerge for the electrons on their way to the backstop when no one was watching which hole the electrons came through. Why had the wave interference pattern appeared for the electrons “seen“ as particles near hole 1 or hole 2 on their way to the backstop?

In this version of the experiment including the light source, one can plot the probability distribution for the electrons arriving at the backstop with both holes open just like before, then repeat the experiment by closing hole 2, and then repeat the experiment again by closing hole 1. If one plots the probability distributions for all the 3 cases for the arrival of the electrons at each position along the backstop, what would this indicate?

When all of the 3 distributions are plotted, one can see that P′12 = P′1 + P′2, meaning P′12 represents the probability distribution for particles instead of showing the wave interference pattern of the previous version when the electrons were not observed near the holes! “Although we succeeded in watching which hole our electrons come through, we no longer get the old interference curve P12, but a new one, P′12, showing no interference!” says Feynman.

“If we turn out the light P12 is restored,” Feynman states, referring to the reappearance of the wave interference distribution when the detector near the 2 holes is removed.

As one can see, it seems to be the case that observing which paths the electrons take turns their probability distribution from that of waves to that of particles, and not observing the electrons’ paths turns their probability distribution from that of particles back to that of waves. How can such a thing be possible?

“Perhaps it is turning on our light source that disturbs things,” states Feynman, suggesting minimizing the jolt given to the electrons by the light photons. To disturb the electrons as little as possible, Feynman suggests turning down the brightness of the light. Dimmer light means fewer photons coming out of the light source, which lets some of the electrons pass through the holes without getting detected by colliding with a light photon. This occurs when one occasionally hears a “click” from the detector but sees no flash at all at either of the holes.

Using such dimmer light to see which hole the electrons pass through, if one plots the probability distribution for those electrons that arrive at the backstop but escape detection near either hole, one gets a distribution indicating wave interference. But if one plots the probability distribution for the electrons that do get detected near hole 1 (P′1), also plotting the probability distribution for the electrons detected near hole 2 (P′2), one sees that the total number of electrons hitting the backstop at every point along it (P′12) equals the algebraic sum P′1 + P′2 indicating the presence of particles for the electrons that do get detected. One only sees the interference pattern for the electrons that escape detection!

Feynman wonders if there may be better ways to avoid disturbing the electrons while observing which hole they go through. He suggests using light of longer wavelengths instead of dimmer light. Such light of longer wavelengths hit the electrons with less momentum to minimize the disturbance of the impact, because the momentum (mass times velocity) carried by a light photon is inversely proportional to its wavelength, meaning the longer the wavelength, the smaller the momentum. Such light of longer wavelengths corresponds to light of a redder color or infrared light or radio waves such as radar.

Feynman explains that it's possible to observe the electrons with such light of longer wavelengths “with the help of some equipment that can “see” light of these longer wavelengths.” But the trouble here is that the wave nature of the light puts a limitation on how close two points in space can be located and still be seen as separate points. If one uses light of a wavelength longer than the distance between the 2 holes in trying to minimize the disturbance on the electrons, one can no longer see the two holes as separate and tell which hole the electrons came through, seeing just a fuzzy large flash around both holes. The longer the wavelength of the light used and the more this causes the loss of which-way information, the more the interference pattern creeps back for the probability distribution of the electrons reaching the backstop!

No matter which observation method one may try, the less precisely one knows which hole the electrons came through, the more P′12 looks like P12 showing wave interference. The more precisely one knows which hole the electrons came through, the more the interference pattern disappears and P′12 looks more like the distribution indicating the presence of particles. David M. Harrison Ph. D., Senior Lecturer Emeritus at the Department of Physics of University of Toronto, explains:

“The conclusion of all this is that there is no experiment that can tell us what the electrons are doing at the slits that does not also destroy the interference pattern. This seems to imply that there is no answer to the question of what is going on at the slits when we see the interference pattern.”

Feynman explains:

“In our experiment we find that it is impossible to arrange the light in such a way that one can tell which hole the electron went through, and at the same time not disturb the [interference] pattern. It was suggested by Heisenberg that the then new laws of nature could only be consistent if there were some basic limitation on our experimental capabilities not previously recognized. He proposed, as a general principle, his uncertainty principle, which we can state in terms of our experiment as follows: “It is impossible to design an apparatus to determine which hole the electron passes through, that will not at the same time disturb the electrons enough to destroy the interference pattern.” If an apparatus is capable of determining which hole the electron goes through, it cannot be so delicate that it does not disturb the pattern in an essential way.”

It will shortly be fully explained exactly why the wave/particle duality described yields uncaused events. But for now, to summarize the central mystery of creation giving rise to the breakdown of determinism, we've seen that although the de Broglie waves are explainable by the mathematics of wave phenomena, they’re not actual waves anyone can ever observe, because whenever anyone attempts to observe them, they stop behaving like waves and are always detected as particles. Whenever the positions of subatomic particles are not observed or observed less precisely, the particles revert back to behaving like waves proportional to the imprecision in acquiring position information.

Since the 1920's, no experimental setup has been discovered that’s proven capable of preventing or circumventing the behavior described. This point will be elaborated in the following chapters.

The next chapter deals with the profound implications of the incredible seeming behavior outlined, describing how it yields uncaused events.

THE WAKING DREAM

In the most important experiment of subatomic theory described in the previous chapter, we’ve seen how subatomic particles arise, having seen the crux of quantum theory in the mysterious “transformation” of the non-material de Broglie waves into the universe’s “material” particles whenever observed.

To stress yet again as the most important characteristic of the subatomic realm, we’ve seen that it's proven impossible to observe the wave aspect of matter anywhere in the physical universe by any method whatsoever, due to the way the waves mysteriously shape shift into particles whenever looked at. Instead of representing physical waves, the de Broglie waves represent probability distributions for observing where subatomic particles show up, as has been demonstrated. This point is emphasized as follows in books such as “Hidden Unity in Nature’s Laws” by John C. Taylor, Emeritus Professor of Mathematical Physics at the University of Cambridge:

“... the complete wave function itself does not have any direct physical significance. It cannot be measured as the electric field is measured, for example. Its phase angle is not directly observable.”

In S. Chand’s Principle Of Physic, one also finds the following summary:

“The de-Broglie waves, though often referred as matter waves, are not composed of matter. The intensity of a matter wave at a point represents the probability of the associated particle (e.g. electron) being there. Therefore, if the intensity of matter wave is large in a certain region, there is a greater probability of the particle being found there.”

In subatomic theory, the matter wave “is a mathematical object that represents our knowledge of the system,” states P. C. W. Davies, Professor of Theoretical Physics at the University of Newcastle, in his book “The Ghost in the Atom: A Discussion of the Mysteries of Quantum Physics.”

If the de Broglie waves, which don’t exist in the physical universe, represent the observers’ knowledge, where else can they exist other than in the minds of observers?

Additionally, as few people can disagree with, if the unobservable de Broglie waves can only exist in the observers’ minds, only another mental construct can “come out of” a mental construct. The universe’s “physical” particles “coming out of” the de Broglie waves must also be mental constructs “arising“ in the observers’ minds out of the possibilities seen by the observers’ minds.

Regarding the way all subatomic particles “come out of” probability distributions representing the observers’ knowledge, Heisenberg has pointed out the way “the transition from ‘possible’ to the ‘actual’ takes place during the act of observation.” This confirms the way it could only be the observers’ minds that create perceived “reality“ (the “physical“ particles).

Regarding the “transformation” of the non-material probability distributions into the universe’s “material” particles whenever observed, Richard Feynman makes the following admission in his lecture notes after having described the double slit experiment:

“No one has found any machinery behind the law. No one can “explain” any more than we have just “explained.” No one will give you any deeper representation of the situation. We have no ideas about a more basic mechanism from which these results can be deduced.”

No one has, and no one will ever be able to explain what causes the “transformation” of the waves into the particles, because the transformation “occurs” in an uncaused manner (indeterminately), as we’ll be seeing why.

In the most prevalent Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics developed in 1925 by Heisenberg, Bohr, Max Born and other founding fathers of subatomic theory, the “transformation” of the de Broglie waves into ”physical” particles upon observation is called the 'collapse of the wave function.' The notorious 'measurement problem' of quantum theory refers to the way no one's ever been able to convincingly explain why and how the non-material wave aspect 'collapses' into a material particle whenever a measurement (i.e., observation) is made. Rochelle Forrester, a philosophy major of Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, summarizes:

“The Quantum Measurement Problem has been around ... ever since Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Max Born and others proposed the Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum physics. As part of the Copenhagen Interpretation they suggested quantum entities such as photons, electrons and other sub atomic particles only come into existence when an observation is made. Before an observation is made quantum entities and their properties, such as electron spin or photon polarization, do not really exist and all that can be known about them is described in the Schodinger wave function. The wave function gives the mathematical probabilities of the state of a quantum entity before an observation is made. The quantum entity only comes into existence and acquires definite properties when an observation or measurement is made of the entity. This is known as the collapse of the wave function as the indefinite qualities [probabilities] of quantum entities turn into definite qualities.”

Before moving on, I'd like to invite everyone to think long and hard about the fact that if the de Broglie waves, representing the observers’ knowledge and being devoid of any physical counterpart, can only exist in our minds, so should the entire “physical” universe “coming out” of them. If anyone may disagree, I'd like to invite him or her to devise a method that lets us finally observe the de Broglie waves themselves directly, to prove their physical existence outside of our minds.